How Physical Archives Keep Cases Cold (and What You Can Do About It)

Sometimes the difference between a conviction and a cold case is a single piece of paper.

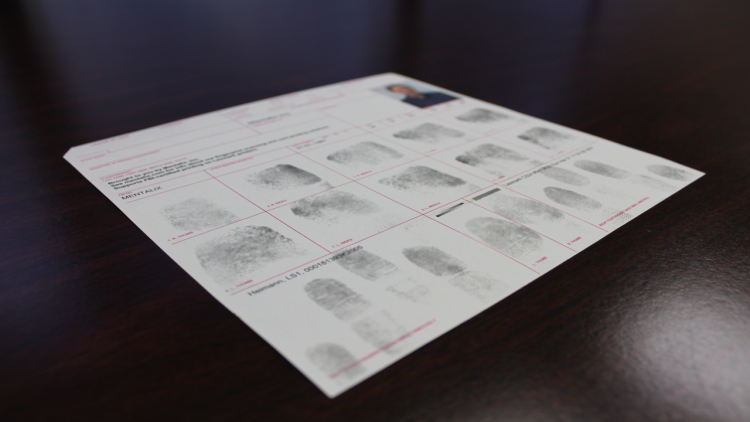

Every day, thousands of fingerprints are submitted to the FBI’s Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS) Database in Clarksburg, West Virginia, and everyday thousands of prints are matched to one of over one hundred million civil and criminal records already stored within it. To put that into perspective, there twice as many individuals enrolled in the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Security department archives as there are people living in the country of Canada.

As a result, it’s easier now than ever to match fingerprints to people, and crimes to perpetrators. But whether or not those prints find a match, and a victim finds justice, depends entirely on how those records are stored.

The Warehouse Dilemma

Long before the days of digital and dial-up, paper was the gold standard for the vast majority of global industries. Filing cabinets filled every office building, patient records collected dust in hospital archives, and boxes of fingerprint cards were stacked in law enforcement agencies across the country.

Storage was as costly as it was necessary, and hundreds of square feet were quickly gobbled up by crates and cabinets full to bursting with documents too important to throw away, but almost impossible to find in the sea of manila folders.

As the world became increasingly paperless, the way we stored our information began to change. Suddenly records that once required fleets of filing cabinets could be stored on a single desktop computer, making information more compact and accessible than ever before.

In July of 1999, CJIS’s new IAFIS database went live, making fingerprint matching easier, faster, and more accurate than previous, human-based methods of identification. For the first time it was possible to submit, match, and store fingerprints in the blink of an eye while older, paper records floundered.

As live scanning caught on, traditional ink fingerprints continued to stagnate, and while some old records were converted into usable digital files, many more remained buried in basements, the fingerprints they contained completely useless in the modern era of computers and Wi-Fi.

But those records still had, continue to have, value. In a country where, between 1980 and 2008 alone, nearly 185,000 cases of homicide and non-negligent manslaughter went unsolved, any one of the tens of thousands of unconverted cards could be the key to putting a murderer behind bars.

Breaks in the Case

Expanding the FBI’s digital database with decades of readily available, if inaccessible, records is imperative for everything from solving murders to identifying victims (of which, between 1980 and 2004 alone, there were 10,300 that could not be named).

Cold case initiatives have seen a slew of convictions as a result of expanding fingerprint and DNA databases, where old, previously unusable evidence can finally uncover new leads decades after the initial crime.

A prime example of what a growing archive can do is the case of 61-year-old Carroll Bonnet, a man brutally stabbed to death in his own home in a deadly 1978 burglary. At the time of the crime, multiple latent palm and fingerprints were collected at the scene, but no matches could be made and the case quickly went cold.

Cut to late 2008, nearly ten years after the establishment of IAFIS. Laura Casey, a technician with the Omaha Police Department, runs a new search against the FBI print database, and within hours she has a match. After closer inspection, the prints were identified as those of Jerry Watson, a man just days from being released from prison after serving a sentence for burglary, the exact motive in Bonnet’s murder decades prior.

On October 17, 2011—33 years to the day that Bonnet’s body was discovered— Jerry Watson was sentenced to life in prison.

The Burden of Boxes

The case of Carroll Bonnet is hardly unique, and similar instances of old fingerprints leading to new suspects is becoming increasingly common. But the success of these renewed investigations is entirely dependent on the databases these searches are submitted to. Given that a whopping three-quarters (76.6 percent) of released prisoners are rearrested within five years of release, chances are good a significant portion of the fingerprints stored in inaccessible folders and filing cabinets belong to re-offenders. Whether or not they serve additional sentences for any additional crimes they may commit could very well depend on if those prints ever see the light of day.

Aside from the obvious criminal implications of an unusable archive, boxes upon boxes of heavy card stock prove challenging in and of themselves. May states mandate the long-term storage of fingerprint cards, and so many years’ worth of physical, criminal records adds up to a lot of floor space.

There’s also the ongoing risk of age, wearing down each paper card, making writing less and less legible with each passing year. And even for the most secure storage facilities there is always the threat of mold, paper chewing pests, flooding, and fire. If fingerprints are one of a kind, then so are their records, and keeping a single copy of any important document opens it up to the risk of being lost for good.

Additionally, the cost of storing and maintaining all those boxes regularly eats into annual budgets and cuts down on storage space for the records and evidence that can’t be so quickly and easily converted into digital files.

And that’s perhaps the core of the physical archive issue – fingerprint cards can be converted, and the problem of paper is hardly a problem at all.

What is card conversion?

Card conversion is the process by which a fingerprint card is converted from a physical piece of paper and ink into an accessible digital file. Generally speaking, conversion is a two-part process that involves imaging the document, then (optionally) transcribing the information on that document into a specialized virtual database.

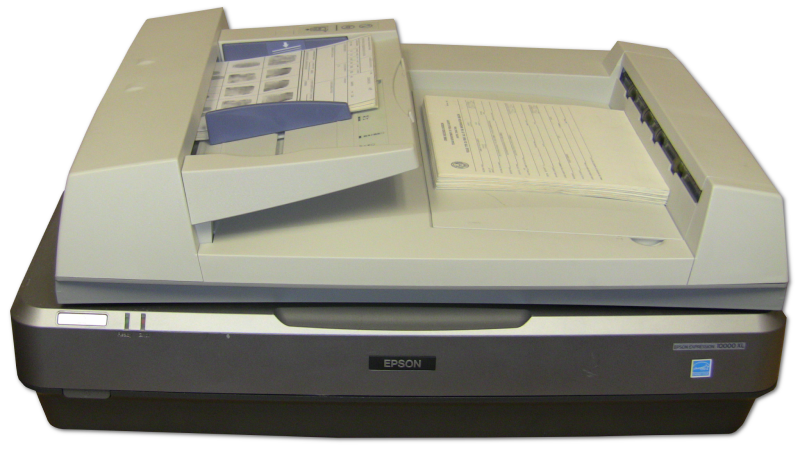

How documents are imaged varies from agency to agency. Smaller agencies might scan fingerprint cards with a desktop scanner on an as-needed basis, whereas larger agencies might deploy multiple high-volume automatic scanners to convert hundreds of fingerprint cards over the course of an hour. Each agency’s workflow is different, but due to strict FBI imaging standards, all scanners used to convert fingerprint cards to digital records must be properly certified.

The input process involves a data entry operator typing the information recorded on a physical fingerprint card into some form of card processing software. This is the most time-consuming, and expensive, portion of the conversion process, as it requires operators to review and transcribe each scanned document.

However, this input step is entirely optional, as fingerprints are searchable with or without their accompanying demographic information being entered separately. In fact, some agencies opt out of data entry entirely, or tap local volunteers to take on the bulk of the transcription to significantly cut costs. So long as a card is imaged, it can be read and accessed, with or without the input phase.

Why should you convert your archive?

It probably goes without saying, but a database is considerably more convenient and efficient than a sea of filing cabinets. Looking up digital fingerprint records only requires a few keystrokes, submissions can be completed in minutes, and millions (yes, really!) of records can be stored on-site without the need for a costly warehouse of perishable fingerprint cards.

Speaking of perishable, converted cards are permanently preserved, can be accessed from anywhere with the proper clearance/connection, and are safe from both the ravages of time and the appetites of hungry bugs.

Additionally, fingerprints that are stored digitally are substantially more useful when it comes to matching, and upgrades in FBI matching software has already made re-submitted prints pivotal pieces of evidence in multiple cold cases.

Digital records are less expensive to maintain than physical records, and converting an archive will ultimately cost an agency less over time. Conversion is an investment not only for the original agency’s future budget, but for the efficacy of law enforcement officers across the county who rely on the IAFIS database to put criminals behind bars.

How can I convert my archive?

Conversion solutions are a lot like fingerprints, no two are exactly alike. But, like fingerprints, there are a few categories conversion solutions fall under:

In-house Conversion

In-house card conversion is an efficient, economical option for either end of the workload spectrum. Small agencies whose processing load is easily managed by one or two employees can benefit from a card scan station that allows them to quickly and easily convert fingerprint cards on an as needed basis, without the unnecessary hassle of contracting out a full-scale conversion center. Conversely, a large agency with a similarly large staff could easily support an in-house conversion center. When it comes to in-house imaging, there are a variety of available options:

Desktop Scanners are FBI-certified flatbed scanners (comparable to your average office scanner) that come without any additional, automatic feeding mechanisms or comparable high-volume features. The most economical of the in-house conversion options, a desktop scanner is best deployed in very small agencies that require only a handful of conversions a month, as a lack of automatic feeding required additional labor and user oversight. When paired with card conversion software, a desktop scanner is the ideal way for small organizations to handle day to day conversion. However, desktop conversion systems can also serve as a backup fingerprinting solution should an agency’s live scan go offline and require users to take traditional ink prints.

An ADF, short for “Automatic Document Feeder,” uses physical rollers to feed fingerprint cards over the surface of a flatbed scanner and into an output tray, all without user intervention. Currently the industry standard, ADF scanners tend to be fast, cost- effective and lightweight. However, because they are designed to very quickly scan a tray of delicate paper cards, the rollers may bend, tear, or smudge documents in the scanning process. Such scanners also tend towards limited capacity input trays, requiring regular unloading and reloading, while their internal rollers and separators must be cleaned frequently to avoid the buildup of ink and dust. Due to ever shifting FBI certification standards, it can be difficult to find ADF scanners that continually make the grade for fingerprint conversion, but they remain a great choice for mid-level workloads and semi-regular conversions.

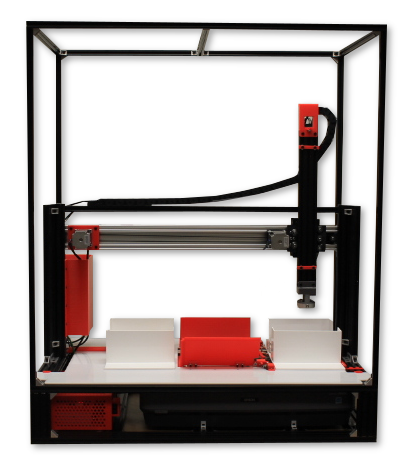

The Mentalix R3 is a robotic document feeder that uses compressed air to guide fingerprint cards across an FBI certified flatbed scanner without physically pulling or bending the documents. While larger than an ADF, the R3’s input capacity far exceeds the ADF standard, and its open undercarriage allows for flatbed scanners to be replaced as imaging certification benchmarks change. Similarly, because there are no fixed rollers or internal feeding mechanics, the R3 can scan a wider variety of documents, and does not require frequent disassembly for cleaning and maintenance. Large organizations, particularly those who require delicate, high-volume scanning without the hassle of constant user oversight, would benefit the most from the R3 and its customizable trays and agency-tailored software. Though potentially an expensive option for in-house conversion, the R3 and its patented conversion hardware make it the most advanced and versatile solution in its class.

Contract Conversion

For massive historical archives and overwhelming backlogs, contract conversion could be your best option to get the job done quickly and securely. Unlike in-house scanners, which require agency operators and staff, conversion contracts cover every aspect of conversion, from shipping to imaging to optional input, without requiring the agency to invest in any additional employees, equipment, or security.

Bar none, contract conversion is the easiest way for an agency to convert a large volume of documents with relatively little agency involvement or long-term investment. But, this convenience comes at a price, as all those additional services can quickly add up. As a result, contract conversion is the most economical when tackling one big, insurmountable backlog, rather than many, more manageable jobs in succession. If your organization is staring down too many documents with too little man power and too little time, contract conversion is the quickest and easiest way to make a molehill out of a mountain.

Why Mentalix?

When it comes to card conversion, there is an endless array of excellent solutions, and sorting through all of them to find the best fit for your agency and your archive can be difficult. At Mentalix, we’re dedicated to ensuring our community’s success, and while we might be a little biased, we know we offer the quality products and unmatched support you need to find the solution that works best for you. If you’d like to update your archive, in-house or otherwise, contact us at info@mentalix.com to learn how.